|

Complete Alan Moore Future Shocks

Rebellion Comic Book: "One Christmas During Eternity" (05/30/2006)

Since the immortal pill no ones ages and no children are born. (M/F AS)

[Reprinted in 2000 AD #271.]

-- http://www.comics.org

|

Complete Alan Moore Future Shocks

Rebellion Comic Book: "The Big Clock" (05/30/2006)

A man fails to wind a huge clock and time stops. (Male AS)

[Reprint in 2000 AD #315, Complete Alan Moore Future Shocks, Time Twister #9.]

-- http://www.comics.org

|

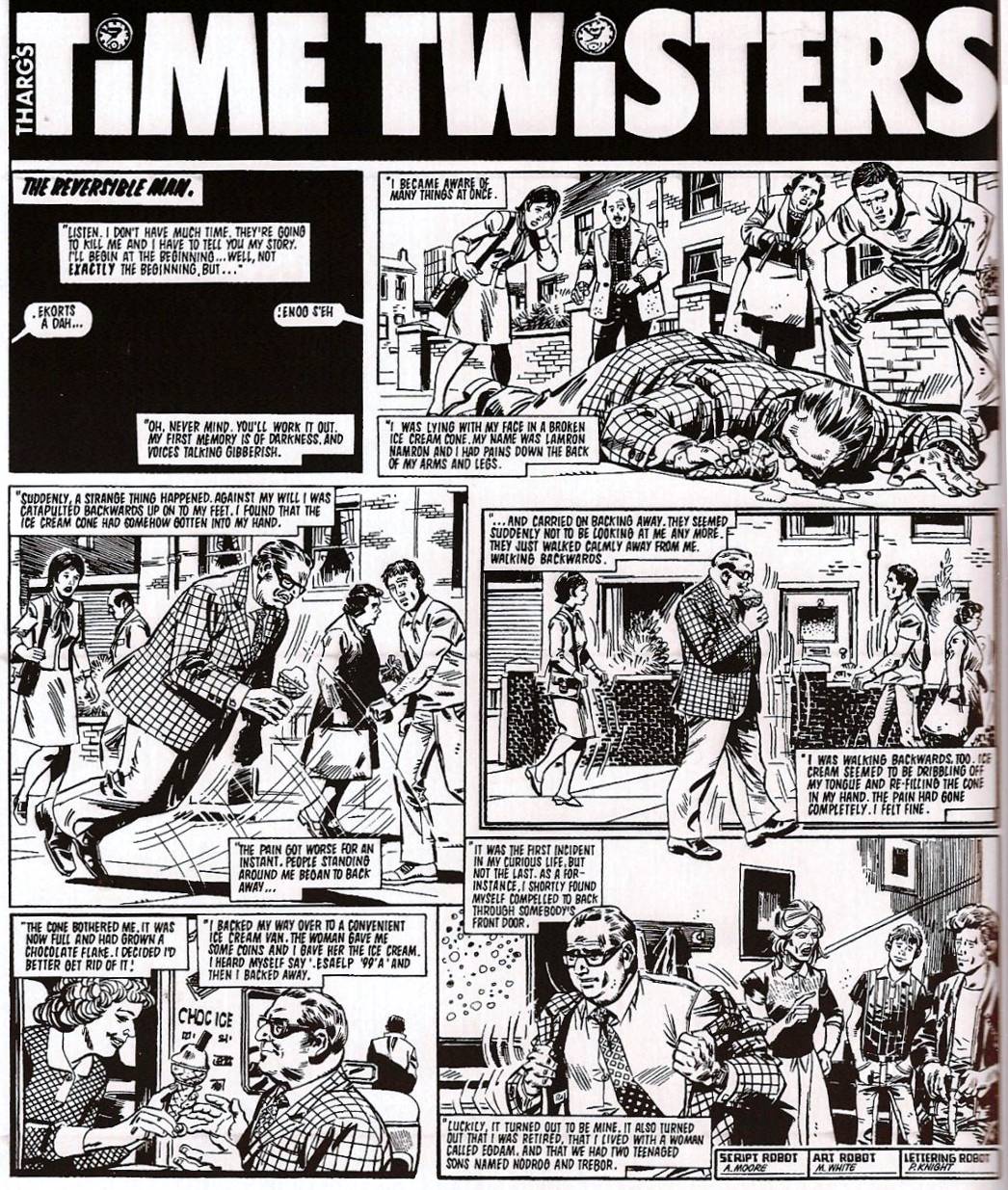

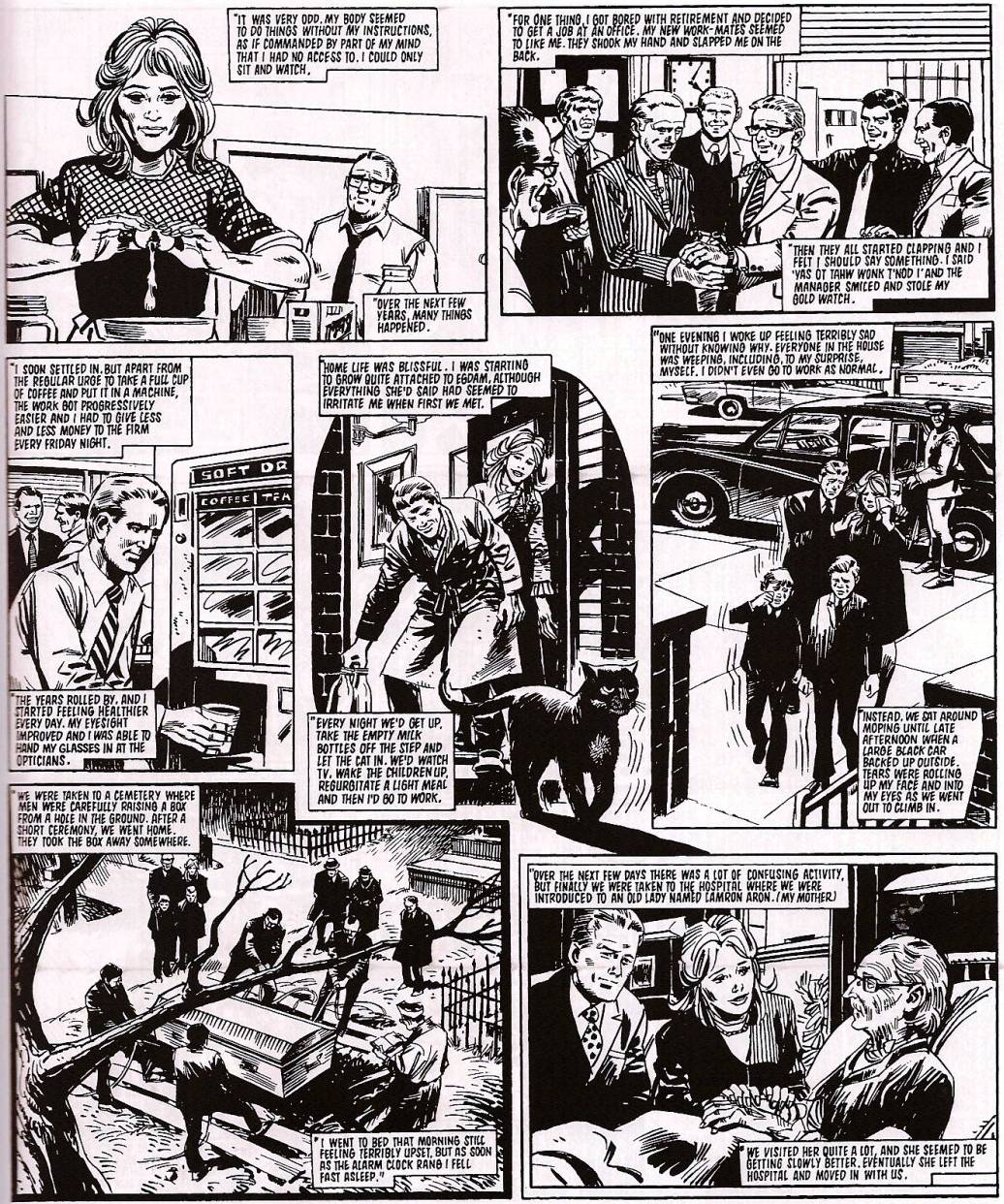

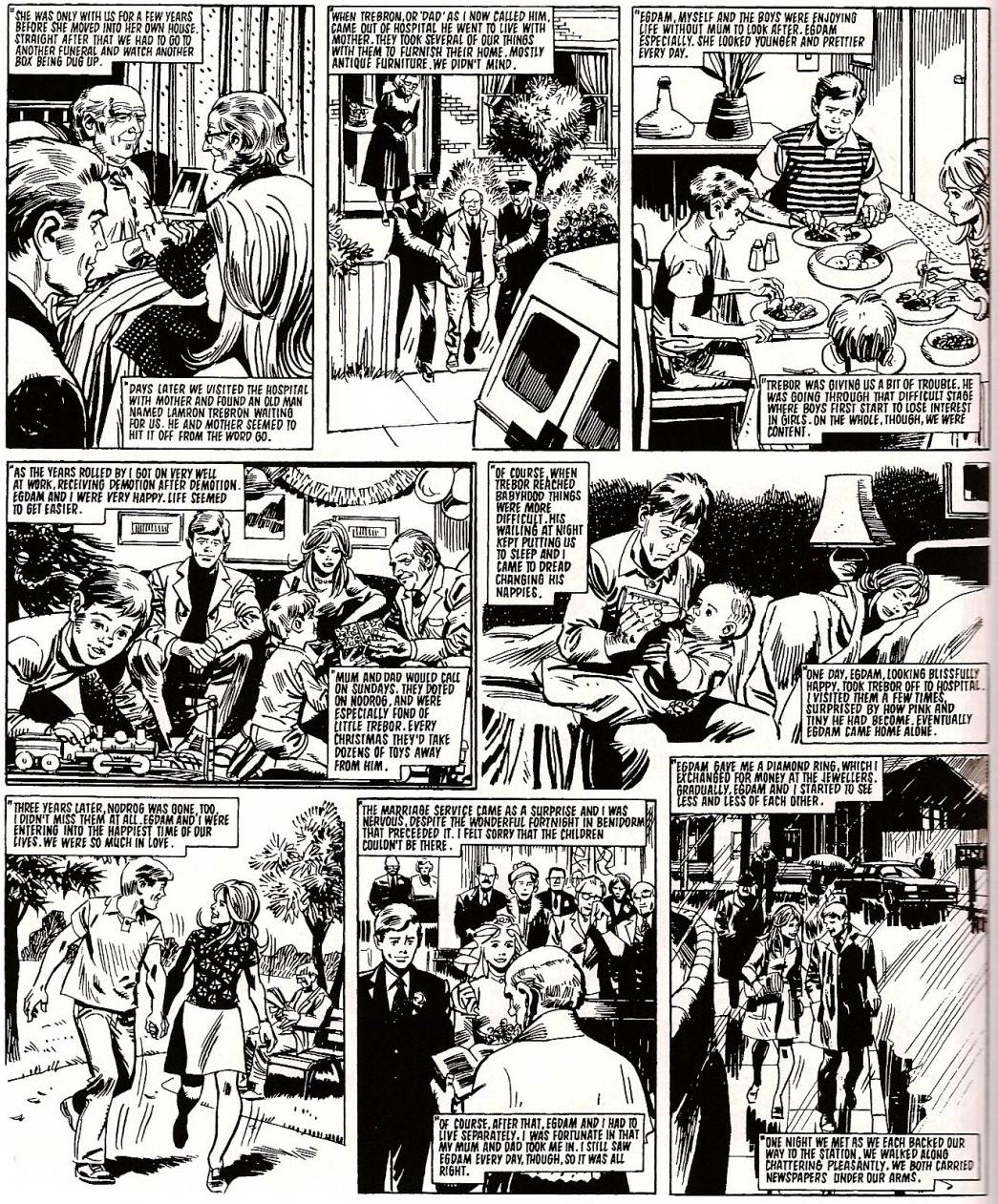

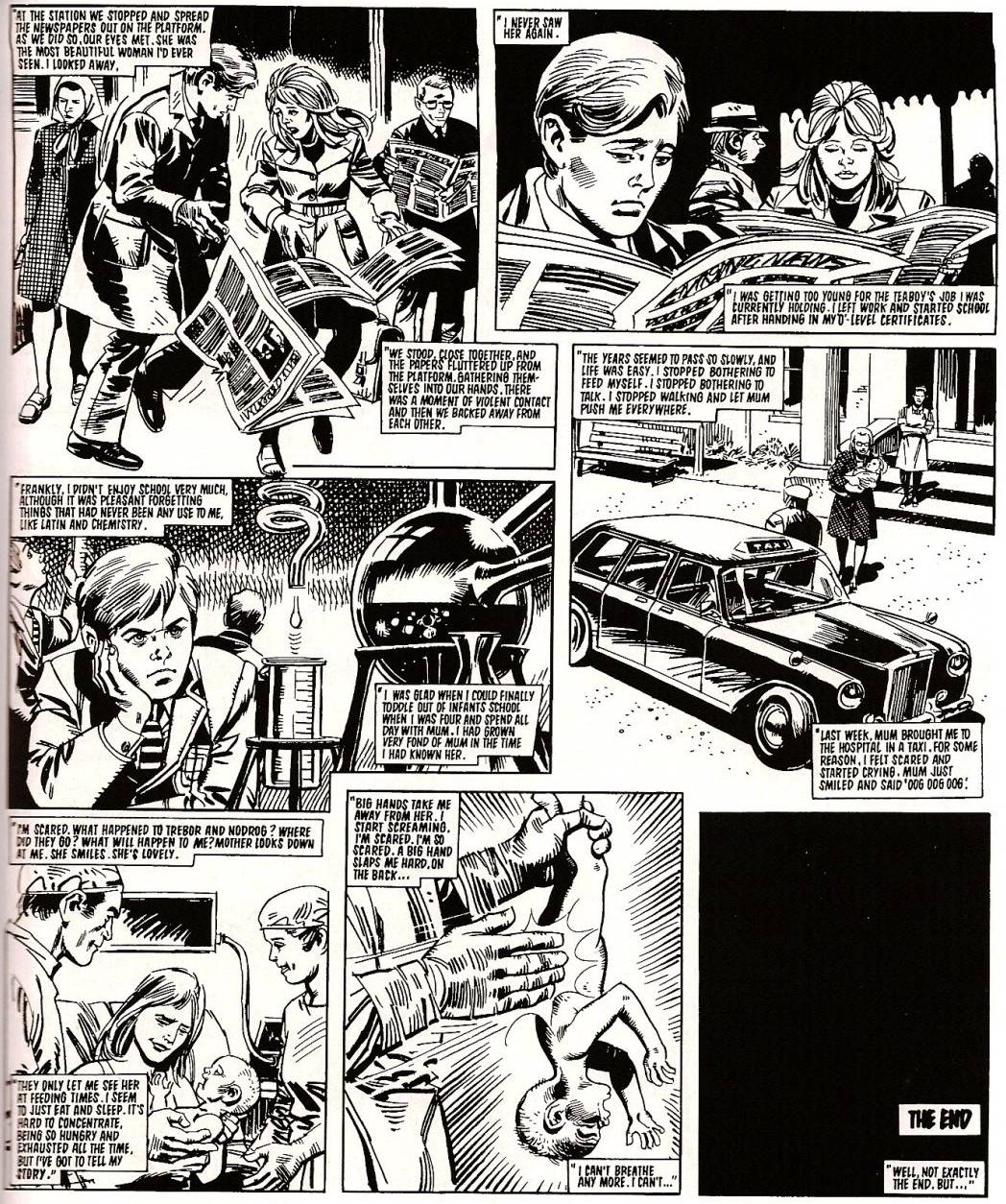

Complete Alan Moore Future Shocks

Rebellion Comic Book: "The Reversible Man" (05/30/2006)

Very early Alan Moore story about one man's and his family's lives - in reverse.

[Reprinted in 666: Number of the Beast #12, 2000 A.D. #2, 2000 A.D. #308, Alan Moore's Twisted Times. ]

-- http://www.comics.org

|

Complete Alan Moore Future Shocks

Rebellion Comic Book: "The Time Machine" (05/30/2006)

In death a man travels back into his past reliving his life. (Male Mental Ar)

[Reprinted in 2000 AD #324, Alan Moore's Twisted Times, Time Twister #2. ]

-- http://www.comics.org

Moore has commented that "The Reversible Man" was "pathetically easy to write," and that he was as a result surprised by its reception, speculating that its popularity was because "the events of our lives become dulled by reputation and it takes an unusual view of them for us to see life and its emotional implications anew," disclaiming that the story's success "had very little to do with me as a writer."

This is, perhaps, false modesty, however - elsewhere he proclaims it "one of the best stories I've ever done," and boasts of how "during their lunch hour, the day that came out, it had all the secretaries weeping."

But even in that interview, where he breathlessly describes the emotional effect of how "an ordinary little scene of two people meeting, their first meeting... becomes their final departure," he suggests that the story came mainly out of his inclination to "do something to see what will happen" and to experiment within the confines of the format.

The story may have been straightforward to write, but the suggestion that there is no writerly skill involved in its success is clearly untrue. Much of the story's power comes not just from the way in which it frames the events of a man's life, but in its specific choices of what events to frame and how to frame them.

For instance, when the narrator's father is dug up and brought to the hospital and eventually goes home, the narrator's mother, understandably, moves out to live with her newly un-dead husband. The narration describes how "they took several of our things with them to furnish their home. Mostly antique furniture. We didn't mind."

The choice of the furniture as a detail for this reversed event - the death of the narrator's father - is a carefully chosen one. There are many things that accompany the death of a parent, but the choice of a mundane, material thing like dealing with their old furniture is a well-chosen one, such that the word "antiques" speaks volumes.

Similarly, the description of how "work got progressively easier and I had to give less and less money to the firm every Friday night" is not the only way that one could describe reversing one's career path, but it's a particularly sharp one, preserving the sense of frustrating drudgery even in reverse.

Occasionally these stories about backwards time have even

crossed over, League of Extraordinary Gentlemen-style ("Merlin," written

and drawn by Randall Monroe, published on May 30th, 2007, on almost

exactly the eighty-fifth anniversary of the publication of "The Curious Case of Benjamin Button.")

Moore's claim that The Reversible Man was "a classic example of one of those stories that just lie around waiting for someone to trip over them and commit them to paper" overlooks the fact that he is neither the first nor the last writer to tackle this basic idea.

In 1922 F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote a similar story in "The Curious Case of Benjamin Button," and mentioned in the introduction that after writing the story he saw a similar idea in Samuel Butler's notebooks. This is a reference to some notes Bulter wrote for his 1872 novel Erewhon (which is widely considered the first work to think seriously about the possibility of artificial intelligence), where he suggested that the people of Erewhon might "live their lives backwards, beginning, as old men and women, with little more knowledge of the past than we have of the future, and foreseeing the future about as clearly as we see the past, winding up by entering into the womb as though being buried.

But delicacy forbids me to pursue this subject further: the upshot is that it comes to much the same thing, provided one is used to it." The idea also appears in T.H. White's revisioning of Arthurian legend The Once and Future King, first published in 1938, in which Merlin lives backwards in time.

And after Moore the idea had life as well - Martin Amis won a Man Booker Prize in 1991 with Time's Arrow, a novel that uses the same basic premise. And, of course, there are the films Memento and Irreversible, which tell their narratives backwards, even though the characters do not experience them that way.

Moore's story works not just because he executed a reasonably common idea, but because he did it well.

Likewise, Martin Amis didn't get nominated for a Booker Prize for nicking an obscure old idea out of a boys comics magazine, but because he chose as the subject for his backwards life a doctor who worked at Auschwitz, describing how he helped create a race, the Jews, first creating their bodies in ovens, then animating them in fake showers, from which he personally removes the Zyklon B pellets, and then finally, for many, perfecting their dental work, giving freely from their own personal supplies of gold to craft fillings for them.

"I knew my gold had a sacred efficacy," the narrator enthuses. "All those years I amassed it, and polished it with my mind: for the Jews' teeth."

This shocking inversion of the Holocaust, where all of the degradations and atrocities become acts of life-giving kindness, gives it new power to horrify by creating a new and startlingly perverse perspective to look at them, much as Moore inverts the major events of life to fill them with new poignancy.

The suggestion that this potency comes merely from the idea and not the particulars of the execution is demonstrably false.

One of the most stunningly bleak panels in

Moore's early career (From "One Christmas During Eternity," 2000 AD #271,

1982):

The power of "The Reversible Man" is worth looking at in context with another fact: it is only the second short story Moore wrote for 2000 AD that cannot be described as a comedy.

In the previous two-and-a-half years of writing strips for the magazine, the only other time he did something decisively non-comedic came in July of 1982, when he penned "One Christmas During Eternity" - a bleak number about a family of immortals celebrating Christmas with their son, in which it turns out that the son is a robot they rented for the day and had to return, and that they do not even get the same robot year-to-year - in Prog 271.

Both stories are elevated by the fact that they have ambitions beyond merely demonstrating a clever idea. "The Reversible Man" does not merely stand out in contrast to the rest of Moore's short stories, though - its quiet poignancy marks it out from the rest of 2000 AD.